The news recently broke that the National Security Agency of the United States has been operating a comprehensive program of surveillance and data collection for national security purposes. The NSA has spent the past six years gathering data on foreign parties of interest. PRISM is a critical tool in the US intelligence community. According to The Washington Post, the program was “the number one source of raw intelligence used for NSA analytic reports.”

However, members of the public have expressed shock and outrage at the scale and complexity of the program. Voters concerned with civil liberties view this expanded capacity of information collection to be a potential danger to the rights and privacy of American citizens. They’re unhappy with the government having so much ability to view into our communications. And those voters have a long, hard battle ahead of them if they want anything to change.

Must Read: What is CISPA and Why It’s so bad for the Internet?

When privacy loses to security

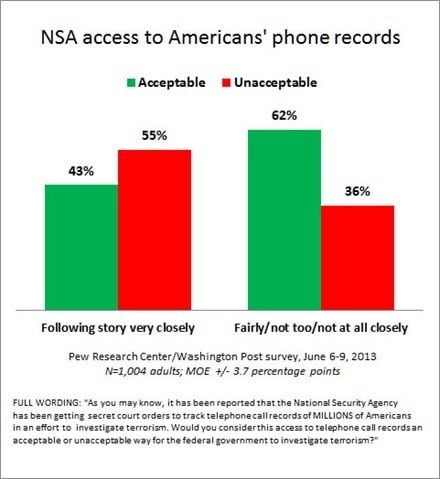

The first problem with trying to protect privacy online is that it is an unpopular cause. The Huffington Post cites a study by the Pew Research Center that showed strong support for the NSA among adults who did not closely follow the PRISM scandal.

62% of those adults considered the NSA’s collection of telephone metadata to be an “acceptable way for the federal government to investigate terrorism.”

Interestingly, among adults who did follow the scandal closely, the numbers were reversed, with a 12% lead of those who found PRISM unacceptable.

This indicates that the average American voter who does not follow these matters perhaps may not understand the scope or seriousness of the powers given to the NSA. “Telephone metadata” does not sound nearly as intimidating to the technologically unsavvy as does a terrorist attack.

And that brings us to the heart of the problem- public perception of the problem. As the Post points out, surveys such as these can dramatically change based on wording, intent, and sample audience. By conducting the survey in different ways, you can get different results.

The same thing happens in politics. By framing an issue in a new light, voters will react differently. Remember Rep. Darrell Issa’s panel of religious leaders when the Obama administration mandated contraception coverage? He chose them to cast mandatory birth control as an issue of religious expression, rather than as one of women’s health.

People do this in politics all the time. It works. No one wants to limit religious expression or make women less healthy. If you can make the debate about something difficult to argue against, you’ve won.

Reframing the debate is exactly what privacy advocates have to worry about. If other parties can change the controversy from privacy and surveillance to security, they’ll likely win. How will the average voter react if s/he believes NSA surveillance to be necessary for survival?

The benefits of being in power

Privacy-minded voters face an uphill battle when it comes to safeguarding their civil liberties. Influencing the course of government and its associated security organizations can be a lengthy and difficult process.

However, that process itself is made doubly difficult because of the secrecy surrounding government surveillance programs. You can’t very well vote against a program which you do not know exists.

Intelligence-gathering operations at that level tend to be shrouded in classified data and top-secret clearances. This is necessary in order to conduct operations securely, but it also creates a conundrum. The only people allowed to have oversight into programs like PRISM are often themselves involved in such programs.

Therefore, these people have the job of conducting oversight over themselves. Some voters might have a problem with the government policing itself, seeing it as an inherent conflict of interest.

In addition, governmental safeguards are ignored at times. For example, The Atlantic reported that the Senate set up the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court in the 1970s as a checkpoint for snooping programs abroad. If a government agency wanted to track a foreigner of interest, it had to go to the FISA court.

In 2001, President George W. Bush decided that the NSA would be free of FISA oversight. They could simply operate without having to go to the court for approval every time.

The government disregarded its own safeguards. Whatever President Bush’s reasons were, such a precedent is worrying. It demonstrates a willingness to use executive power to overrule an attempt by the Senate to check the agencies’ influence.

What you can do to help

So what can we do? How does an average American voter help change such massive programs that seem far out of our control?

Fighting for privacy is a lot like fighting for any other political cause. There are a couple different ways of helping out, depending on your resources and spare time.

First and most importantly, vote for candidates who take privacy seriously. If enough voters value their civil liberties, then politicians will react accordingly and fight for them in Washington, D.C. That’s how democracy usually works.

Secondly, donate to worthy causes. You can give money to politicians and advocacy groups who work for these kinds of causes. The Electronic Frontier Foundation is a great group that does a lot of important legal work protecting your rights online. A donation to them wouldn’t go wrong.

We’d recommend this course for non-Americans who cannot vote for our candidates. It’s a good way to make your voice heard even from abroad.

And lastly, spread the word. Help educate people why privacy matters, even when you don’t have anything to hide. Size is power in politics. A million voters have more influence than a few hundred.